-

The Stepwise Movements of Aspiring Migrant Women to Cities

Sondra Cuban © 2023

This post focuses on bridging my two studies of Mongolian women and their internal migration within Mongolia and their intraregional migration to South Korea. These studies connect both types of migrations to women’s spatial mobility in a “golden urban age” that carries certain advantages (see, Chant, 2013). Despite the many inequalities of urban life, migrant women leverage their gender and nationality within Northeast Asian global cities to develop the region, themselves, and their families’ livelihoods. Mongolian women’s stories are a case in point.

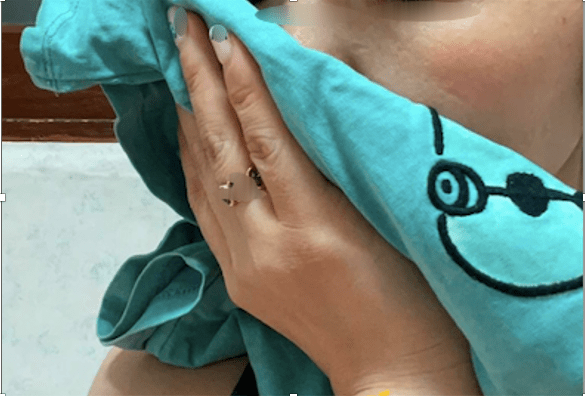

Talisman: a marmot ankle bone anklet on red string given to a participant and her daughter by her father for protection in South Korea I observed a step migration pattern for Mongolian women and their families moving from the countryside to capital cities, in this case, Ulaanbaatar and Seoul. Migration researchers (Paul, 2011) have documented how individual migrants have been “working their way up a hierarchy of destination countries” gradually for the purpose of work, studies, and livelihoods.

As an example, one young participant in Seoul who was born and raised in Ulaanbaatar by a single mother described her migration as part of a stepwise transition upward with South Korea as a transit zone for her and her husband, who was “also from a developing country.” She mapped out her situation which consisted of onward moves to western countries:

“In Mongolia we are developing step-by-step but not like Korea…We will stay in Korea, that’s the 5-year plan…[the question is] if we can still fit in to Korean society or should we move? Then we will feel nomadic. If we move to Canada, we will have to survive…we were looking forward to Australia and did the research—my husband speaks French, English, Korean. There are more opportunities in Canada”

Since the 19c step migration focused on people inching closer and closer to urban areas in short-distances in their own countries, first from remote settlements, or hamlets, that they were born and raised in to towns and then to cities—which expand to accommodate waves of growth, but also lead to overcrowding with the need for onward migration. In Mongolia, bags and sums confer these village and county boundaries. This movement, along with land owning legislation enabled Mongolians from the 1990s to move to more urban areas. .One woman’s story, Tsolmon reflects this pattern. As a young girl she went to a village school and then as an older teen moved to help her grandmother who was a herder. It was here that she met her husband, also a herder. In 2001 there was a dzud (an environmental crisis consisting of dry summers followed by severe frozen winters that killed the herds). After losing their livelihoods, her and her husband moved to Ulaanbaatar to start a new life, with her grandmother following her. Her ultimate dream was to live in South Korea where her brother lives. He told her she could “find work easily there and get rich.”

deadly effects of dzuds on herds and herders, @cc Although these smaller movements within Mongolia are not normally viewed as migratory in and of themselves, I examine them as part of a larger pattern of rural-to-urban migration. I show that Mongolian women, over a lifetime, are moving to places that are more densely populated and urbanized for better livelihoods. They move with or, before or after family members in a chain of family labor migration, to larger and larger urbanized areas, and from there, to metropolises like Seoul, while other members stay behind. This is happening despite government policies to reward internal migrants for returning to the countryside. Or on the other hand, restricting registration for permanent residency in Ulaanbaatar. The drive for daughters to migrate for education in particular to Mongolia’s cities is strong, and because of the large family structure and dispersed networks, they can maintain a sense of being united despite the distances. Over time I discovered that participants and their families were moving closer to urban centers especially Ulaanbaatar which is a school and work magnet for Mongolians across the country.

This IOM employment report on internal migration (2021) surveyed migrants and found a similar pattern to my study:

My study traces 60 Mongolian women’s migrations, not only through rural and urban geographies, but across generations and over time. Families, both nearby and afar, embed members and anchor one another in a type of chain of relations that propel their migrations as part of a progression of movements to cities to secure greater livelihoods (Grzymala‐Kazlowska & Ryan, 2022).

air dried beef (borts) was often given to young women to take to the city from the countryside by herder parents Along with chain migration comes additional social, cultural, environmental and engendered changes that are important, which are part of a lifespan perspective on migrants, for example, the period of time when young women leave the countryside and their motivations and decisions for moving to larger and larger places in young adulthood and then into middle-age. My research did in fact take a life history approach of inquiring about family situations including where they were raised as well as the livelihoods of their parents, and their pathways into adulthood.

Milk and cheese is an important gendered work for herding women and can be taken anywhere. Milk and milk products have special significance in Mongolian culture, including for eating, drinking, and using for good luck when traveling. All travelers and guests are given cheese when they enter gers and I carried milk with me to interviews in Korea to give to participants

Among the 60 participants, there was an intergenerational shift of Mongolians moving from the countryside to the capital city, Ulaanbaatar, and then from there to a nearby and popular destination in the region, South Korea.[1] With a dispersal strategy of family members across two or more countries, such as this, families and households could survive the difficulties of a lack of infrastructural state support and a neoliberal economic system that failed to buffer the shocks of the market on individual and family life in Mongolia. And the center of most of supports in Mongolian society is based within the family unit.

[1] While I did not shadow single participants moving from the countryside to the capital city and then onward to Korea’s capital, and separated them into two cohort samples, one internal and the other intraregional, I could still make comparisons across the two groups as they and their families moved towards an urban existence.

Family resources, accumulating over time through different and dispersed family members and their networks across Mongolia and in other parts of the world (including South Korea), fueled this sample’s human capital, driving them from Mongolia to South Korea to acquire more capital, pay off debts, and setting in place aspirations to continue to move homes. It was clear they had a more positive view of globalization on their lives, in terms of improving their education, career opportunities, life capacities, and which has also been found in other studies of Mongolians (see, for example Horne & Davaadorj, 2021). But it wasn’t a simple formula. While the two samples differed in these respects, in other ways, they were not so very different from one another. For example, the younger women in both samples were similar, especially with regard to their educational capital and aspirations.

Mongolian women, in many respects fit the definition of “aspiring migrants” who “imagine futures away from home.” (Bal & Willems, 2014). By this, they “aspire to have the best of both worlds by combining local realities with global possibilities.” In this case, Mongolian women move to cities and metropolises to enlarge their scope of opportunities. While aspirational migration is considered to be an economic response, intrinsic qualities such as self-care and self-development also play roles and many participants expressed that they had developed maturity, cosmopolitan attitudes and multicultural outlooks and competence in dealing with diversity. And while normally aspirational migration is associated with high skilled migrants, those with less education also expressed similar motivations and sentiments. One internal migrant for example, with a high school education was originally from Altai city in the Govi Altai province and had lived in Ulaanbaatar since school age. Her aunt gave her a folktale book to bring with her, and she in turn gave this book to her niece telling her that it “says everything. You understand the world. The book teaches us everything.” In this way, according to Dr. Shurla Thibou (pc, 2023), she was “paying it forward.”

Mongolian folktale book She was currently saving to study in South Korea and planned to go because of the “good universities.” But there were other factors that she took into account, especially her gender and race. She subscribed to Mongolian women youtubers in South Korea that influenced her thinking about where to study and live. When comparing alternative destinations, she reflected that in Korea:

“they will accept me as an Asian woman. If I go to American or European countries, they would say, ‘oh she’s an Asian woman.’ Because of COVID 19, they don’t like Asian women—it’s scary to study in western countries. I prefer Korea.”

It has been shown that living in an urban area increases global information flows and therefore influences aspirational migration. In one study those participants who were residing in Ulaanbaatar were more attuned to social media and information flows from around the world, including being conscious of the ways that Mongolia was covered in the press (Horne & Davaadorj, 2021). Yet it goes without saying that while this may be true across the board, rural families in Mongolia were also attuned to globalization pressures. In my study, for example, the herding families I spoke with were well aware of issues associated with migrating to Ulaanbaatar and they discussed the importance of sending their daughters there to get a higher education. In one case, a young university Law school graduate had herding parents who supported her through her studies. She said:

“They supported me. ‘The girls have to study at university, to get a major to prepare. It’s much better for your future life’…. My parents are thinking now it’s a kind of problem— most of the herders, they have too many cattle— the field is crowded and not enough fields, 17 million cattle and 3 million people—too many people. Looking after animals is a hard job. My parents think so. Girls have to study in university and work…”

None of the participants saw their futures in rural areas. While some participants thought they might return to their communities to ‘give back’, with small businesses that could contribute capital, this could only happen after they had acquired large amounts of resources to move there. For the most part every participant saw themselves as struggling to earn their own way in the world, as individuals and as part of a family unit, rather than as part of a national collective goal. These aspirations embodied neoliberal goals that were embedded within the current Mongolian economy and society (as well as in the global economy), and they were also internalized as inherent to Mongolian cultural mobility, for example with the idea of the ‘camp’ that accompanied histories of displacement (see for example, Myadar, 2021)

For these participants the city was a ‘passport’ to a better life and a place of dreams, like this participant who was a tour guide and showed me the inside of her suitcase.

The next several posts will focus on the precious objects that participants brought on their stepwise journeys to urban centers, as well as their communication within their transnational family members and compatriots, the educational drivers in their lives, in addition to the role of climate change.

-

Mongolian Women on the Move to Korea

copyright ⓒ Sondra Cuban 2022

The Korea Study

Figure 1

Thirty Mongolian women with diverse backgrounds, both documented and undocumented, were interviewed about their reasons for migrating to South Korea (ROK)—with the world’s largest diaspora of Mongolians[1]. The participants were interviewed around the Seoul metropolitan area where most migrants live in addition to one smaller city, where six participants were interviewed[2]. They ranged in age, similar to the internal migration cohort, from their 20s-60s although most were in their 30s and 40s.[3] This intraregional study sheds light on the complex reasons that Mongolian women migrate to Korea, a nearby country, including underlying push-pull factors (socio-economic and cultural) as well as policy initiatives.

The research highlights the women’s strategies for survival, their agency, and their contributions, as well as the sacrifices they made in the process of migrating to Korea from Mongolia. In Figure 1 for example an undocumented participant smells the pajamas of her three-year old who she left in Mongolia with her sister. She had difficult jobs, namely cleaning, and in her spare time spoke with her family in Mongolia. She asked her sister to send the clothes of her three children, so she could “smell their scent” which compensated for her lack of communication with them, especially the three year old and 5 year old who found it tough to fully express themselves on Facebook messenger, a popular app Mongolians from all over the world use to communicate with transnational family.

Interestingly, this participant and others residing in Korea, lived in Ulaanbaatar before migrating to Korea, or, they had been born and raised there—demonstrating a stepwise approach to migration directly from the largest city capital to another capital in a popular country for Mongolians. More patterns were discovered with the following themes representing both push and pull factors for Mongolian women’s migrations and mobilities:[4]

- Korea’s Hidden Manufacturing and Service Sectors: Undocumented women and those on short-term visas experienced economic collapse and problems in Mongolia that propelled them to migrate to make money in a country that paid them what they thought their labor was worth. They came on travel visas and overstayed, working in the lower end of Korea’s manufacturing industries, including factory work (retail especially), but also service (cooking and dishwashing in restaurants), as well as cleaning apartments or other buildings as well as cleaning in Korea’s tourist industry (hotels). Mongolians could easily blend into the hidden labor force and their body work was highlighted in these jobs similar to their husbands, who were often in construction or moving jobs. These jobs were easy to access through the grapevine and regardless of visas, this work was in demand and could be done part-time or full time, and even on working vacations

- Korea’s Advanced Education System Matched to Visas: It is well known in Mongolia and across Asia that Korea has a reputable and accessible higher education system, which has contributed to the country’s high skilled workforce, particularly for women. Yet many levels of universities existed and which were magnets for Mongolians. They made enrollment easy, as long as prospective students paid. Those who were already highly skilled could enter Korea’s advanced post-graduate system and a number of participants enrolled in Korea’s universities to receive a master’s or PhD degree, as well as to work, have family there, and live. Some programs were designed specifically for them, and they only met on selected days of the week, especially Saturdays. Those students could stay long-term in programs, especially in private universities. They often applied by themselves, but were buttressed by educational brokers and different types of visas that could shift and which enabled them to enter the country and stay short-term. In many respects, student visas were highly gendered in this way, similar to marriage migration routes. Mongolian women however had to pay a high price to learn in Korea and pay tuition fees for advanced degrees, not to mention the language residency programs they also had to attend (and pay for) and they had to work under the table to maintain their daily lives. These “visa universities” while attracting Mongolian women as a way to improve social mobility, could also be a drain on their finances

- Korea’s Expansive Social Infrastructure for Development: Korea’s health care and medical systems and services were advanced in comparison to Mongolia. Mongolian women often saw Korea as a safe and healthy place to raise children in particular. A number of Mongolians critiqued the Mongolian government for failing to meet their needs and those of their families and many wanted a safe and secure place to develop and use their skills/expertise and to increase their capacities and livelihoods. Mothers were likely to stay in Korea if their children were born there and they could send them to childcare as early as the infant stage, which was more complicated in Mongolia. Also, they could observe and immerse themselves into a middle-class culture of care as well as a public space that was safe and ordered. Even if they felt like outsiders, they preferred that to feeling disregarded by the Mongolian government and its lack of infrastructure for development and social welfare. While legal mechanisms were in place in Mongolia to provide certain social and civil rights protections for women, in practice many participants felt short changed.

- Bi-Lateral Mobilities for Transnational Families: Migration was also heavily tied into family obligations and remittances. In particular, marriage migration could be an anchor for an entire family unit in Mongolia especially when that migrant became a Korean citizen. Also, remittance houses were afforded and built in Mongolia from jobs in Korea. Those who were labor migrants and their family members might move back and forth from Korea especially with travel visas to work and it was widely expected for families to transit through Korea. Mongolians often referred to their host country as a “Korean dream” for the wealth that could and did accumulate among and between families and households living in different countries. Korea was Mongolia’s third neighbor in this sense, economically, socially, and culturally. Families often told each other about life in Korea, ate Korean food in Ulaanbaatar, and knew where to go once landing there (especially to Mongol town), and a number of participants had been to Korea, on working trips before finally settling there. Children and families might move back and forth between countries and visits were frequent before and after the COVID pandemic policies came into effect.

Barriers and Support in Korea for Mongolian Women

Barriers comprised government rules surrounding visas that didn’t make sense or were not explicit especially around non travel visas (there were so many categories). Cultural barriers such as language were also prevalent. Even though Koreans felt that Mongolians had similar physical features to them as well as ancient common histories and could assimilate, they still felt like they were treated as outsiders especially when it came to speaking and interacting in Korean society. They thought of society in Korea as closed to them in many ways and although they tried to ‘pass’ when Koreans discovered they were Mongolians, they could be difficult. Food too was another factor that made it difficult to integrate into Korean society. Fish and seafood for example are not considered to be Mongolian favorites but were pervasive in Korea. The food was spicy, sugary and abundant and many participants said they gained weight after settling in Korea, or, they developed allergies. Other barriers were expensive rents that limited their daily lives and caused them to commute over an hour just to get to work because housing was more affordable on Seoul’s outskirt districts. Additionally, Mongolians were often struggling to afford basic Korean amenities as well as to save and support their families in Mongolia and in Korea. Last but not least sometimes entrepreneurial investments within the Korean Mongolian community could cause difficulties within relationships and of reputations.

Supports consisted of friends/colleagues that became surrogate family in Korea—working and sometimes living together or nearby, family back home who they contacted frequently, as well as language teachers, churches, gatekeepers, and resources in Mongol town, and also, husbands who followed their wives and supported them to study and work. Finally, the K-12 school system and childcare were also critical supports for Mongolian mothers with children born or raised in Korea and they often felt it was an anchor for them to settle there. Generally, Mongolian women all said that their time in Korea improved their circumstances in multiple ways and they believed they had made the right decision to migrate there.

Mongolian Women in Korean Society

It was clear that among the women I interviewed, regardless of their status as marriage migrants, workers, or students, they were the backbone of Korea’s economy, as were other migrant groups—taking jobs no one else would, especially in cleaning. A number of the participants were required to work just to survive life especially in and around the expensive capital city Seoul. Mongolians worked in Korea to buy or build apartments or homes in Mongolia, save, and bring their families over, as well as start new lives. Most undocumented participants thought of Korea as a transit place to make and save money and then return while those documented participants who started families were more likely to consider Korea as a permanent home since their children were born there and spoke the language. Other participants had planned, or aspired, to move on to western countries after Korea. Separation and distance from family were not as much of a norm among these participants, unlike the internal migrant participants, because they were raised in Ulaanbaatar and stayed there together before a member migrated. A number of the participants though would send their children back to Mongolia to learn the language and adapt to life there because they had planned to return anyway. Undocumented participants, a little less than half of the study sample, were often stuck paying high prices for health care in Korea and had many other expenditures associated with leaving children back home, not to mention the emotional costs of being separated from them, as this parent shows. Apart from one or two participants, however it was clear that the quality of their lives had improved in terms of socio-economic outcomes for themselves, their children, and family back home. However, psychological outcomes were not necessarily viewed as better, and symptoms could actually worsen over time because the women lacked enough supports needed to thrive in Korea. Mongolian women, regardless of whether they lived in Mongolia or Korea, often thought of Korea or some other country as an inevitable next step for their livelihoods.

[1] See 2022 figures for ministry of Foreign Affairs (South Korea): https://www.mofa.go.kr/eng/nation/m_4902/view.do?seq=19

[2] 6 participants were interviewed over Zoom prior to the summer of 2022, four of which were added to the corpus data of Korean migrants

[3] The interview methods were similar to the internal study and with the same interview instrument. Different though, I went to visit the participants in their homes, cafes and workplaces.

[4] COVID and pandemic policies in Mongolia and Korea were another im/mobility factor that will be discussed in future articles and papers

A special thank you to the Jack Street Fund for Mongolia which funded both the internal study on Mongolian women migrants and the intraregional study in Korea, as well as my fabulous colleague, Martina Sottini (soon to be “Dr.”) who helped with contacts and advice on doing research in South Korea

-

In Mongolia: Women on the Move To the City

copyright ⓒ Sondra Cuban 2022

The Mongolia Study

Figure 1 A close look at this windowsill (Figure 1) in an Ulaanbaatar city center room reveals dung incense in a glass vase. It is lit by the women who use this office as a meeting and workspace. And in smelling the fragrance, they remember the countryside, from where they came. A participant explained to me that it reminds her of her roots and good memories. These women’s engagement in this ritual neither romanticized country life nor exoticized the dung as a pastoral symbol; instead they connected it to their labor and livelihood of gathering dung for fuel as girls, and as adults, to culture, such as Mongolian poetry—a far cry from the glorification of the Mongolian horse with its masculinized and nationalistic associations. It was not uncommon for me to see dung incense holders sold in regalia shops or in public bathrooms, where women work.

It was in this space that I interviewed thirty women, all of whom originally were born and raised in the countryside and moved to Ulaanbaatar, with arrival dates ranging from the late 1980s to recent. From many of them, I learned about the pull of Ulaanbaatar and how it operated in their lives, as a magnet especially after middle/high school. A number of the participants came from generations of herding families. This study was sponsored by the Jack Street Fund for Mongolia and the American Center for Mongolian Studies and the Henry Luce Foundation. From additional ethnographic group interviews of herders and herder leaders located in two different areas in central Mongolia I learned about push factors in herding families’ lives propelling them to move to the capital city– many of their adult children migrating to Ulaanbaatar for education and work.

This study uncovered complex factors for the contemporary internal migration of Mongolian women from the countryside to the capital city. The ages and backgrounds of the women varied widely, from their 20s-60s, and while a minority came from well-resourced families, others were impoverished. They arrived in the capital from a number of provinces and villages, some of the participants being displaced due to climate change and other factors while others voluntarily chose to move there[1]. Their routes however to Ulaanbaatar were not necessarily direct and there were smaller movements that represented a rural-to-urban migration pattern in addition to circuitous movements and detours that stood out in their stories. While many of the women desired to return to the countryside, and some of them temporarily did, they lived in the city for the meantime, and were both settled and unsettled in their decision to stay put there. Their situations however weren’t characteristically ‘urban’; they visited the countryside to see relatives, although infrequently due to their work lives. And they also visited city parks and lived within and around kin in ger districts, retaining precious artifacts from the countryside and bringing their gers and living in these, or other ones as well. They participated in countryside rituals, such as lighting dung incense, all of which compensated for a rural experience to the extent that they could. I asked the women to describe the precious objects that they brought with them from the countryside, both ephemeral and permanent, and to represent their daily lives moving around in the city in maps they drew for me, including their favorite places, to understand the full range of their mobilities. The stories they shared, together, revealed patterns which are detailed below as themes. However, their stories also raised questions about the diversity of Mongolian women’s livelihoods and their aspirations as they are affected by the systemic barriers that restricted their movements. Additionally, questions surfaced about the homegrown supports they developed within their personal networks, which was also evident in their stories, and the degree to which they enhanced their autonomy and capacities. Last but not least it was not clear whether or not Ulaanbaatar was their last stop as a number of them dreamt of going overseas and Korea was specifically mentioned in several of the interviews. Overall, this was an extremely rewarding experience, as I was able to uncover narratives of engendered internal migration, collected images of this experience, and heard stories of struggle and resiliency. I am heavily indebted to the women who participated in the study, who took the time and energy to talk to me and share their lives, as well as to the supporters and sponsors of this project.[2]

Methods

- Interviews with six herding families and three herder leaders (bagiin dargas) as part of a field research course on climate change and herding including topics of women’s work and education. Notes were taken of these interviews, some of which were triangulated by additional notes of group members who visited these and other families in addition to recordings[3]

- Academic and expert consultants: Lectures by professors, managers of research centers, and doctoral students during the field school as well as expert interviews with NGO consultants in 2021/22 via Zoom and in person on migration issues in addition to consultant interviews, including with the Asia Foundation, Ms. Tsolmontuya Altankhundaga, and my research sponsor, Dr. Narantulga Bataarjav, National Academy of Governance

- Interviews with 30 women about their rural-to-urban migrations, using a structured interview instrument with 5 biographical questions (name, age, province/village born and raised as well as early family life, schools, parents/grandparents), as well as 8 additional questions about their migrations, adaptations, and aspirations, including questions associated with the precious objects they brought with them and ‘maps’ they drew of their daily lives in Ulaanbaatar

- Ethnographic Observations while living and doing research in Ulaanbaatar, from the field school and a family who hosted me in an outlying ger district, that was from the countryside, with a journal and photographs

- Photographs of Precious Objects of the participants as well as those artifacts in the interiors of gers (of herding families), to understand family life, the labor of women, and hybrid customs and innovations, as well as traditional culture and meanings

- Maps of Women’s Daily Lives and Movements in Ulaanbaatar from 30 interviews

Themes: Push and Pull Factors of Women’s Internal Migration

- Separation and Distance in Girlhood Impacted Migrations and Mobilities Migrations occurred in small steps, first within the family, that started with children going to school. Typically, once a girl reached 6-8 years of age (depending on education policy in Mongolia at the time) she would go to school in a village sum (a county), either living in a dorm, moving in with relatives, or with her mother in a rented apartment—the former two options, prevalent during the Soviet period especially if the parents were nomadic herders. After democracy and the market economy expanded, the latter case was more prevalent, where the mother lived with the children, or child during the week. The distance and separation of the mother from her herding life (and other children and partner) during most days of the week, initiated the first step of migration for rural women and girls. From girlhood to adulthood, policies on school attendance, enrollments, and participation were changing and dictating many of their experiences, thus impacting distance and separation practices of girls, regarding family life and migration.

- Higher education as a driving factor for young women’s migration to Ulaanbaatar It became clear, early on in the study, that the capital was a magnet for young rural women in attending university and technical colleges, and it was typical among the participants (as well as in herding families I interviewed) to expect daughters to go to Ulaanbaatar to get a higher education. This appeared to leverage the family status as well as assist with remittances back to parents and symbolized a daughter’s progress. Educated women often moved other siblings to Ulaanbaatar, and it was not uncommon for parents to later follow them in older age. These young women often arrived directly after school or within a couple years of graduating middle or high school. The uncertain condition of the global economy in Mongolia as well as the unpredictable natural environment, produced compensatory strategies of families (including accumulating livestock as part of insurance for tuitions and daily needs of the university student). Despite problems and issues associated with migrating to the city for a higher or vocational education, all participants declared that their livelihoods were much improved. This was even more of the case for those participants, (about half of the sample) who were highly skilled. Several of these participants obtained professional posts in Ulaanbaatar, among which were lawyers, academics and teachers.

- Women’s Labor and Jobs Dominated their Adult Lives Nearly all participants in the study worked for pay in Ulaanbaatar, regardless of their ages. These 1st generation internal migrants also worked extremely hard with schedules that would be unmatched in any core country, and which is typical in emerging economies. These women could be viewed as the backbone of Mongolia’s economy and Ulaanbaatar’s continued urbanization, and they stayed put in the city in low and mid-level jobs, to ensure it was running and thriving. The women’s work in the study in large part represented Mongolia’s burgeoning service economy with jobs the participants had such as cashiers and receptionists, but also its industrial aspects with a number of participants working in factories and outsourced cottage industries. But the participants were also engaged in entrepreneurship such as selling products especially clothing through their family networks. Moreover, there were a number of participants who drew on their high levels of education for professional posts. The family’s labor hinged on the intense work of women, who multi-tasked and held numerous jobs, including caring for children while working full-time. Additionally, stories revealed discrimination within Ulaanbaatar’s labor market, including employers not hiring women due to being over a certain age or expecting that prospective employees would become pregnant, despite these practices being illegal. Over a lifetime, many participants became inserted in the lower ranks of the labor force and moved horizontally rather than vertically within it. Yet the declared that they were making more money than they would if they were to stay in the countryside.

Summary Points: Internal Migratory Routes of Mongolian Women

- Steppe to school was the initial migratory move in girlhood and for mothers.

- Draw of a city education and urban economy accounted for secondary young adult migratory routes to the capital. After graduating they stayed on for jobs and because of new networks of family and friends, and they may move back to the countryside temporarily.

- Women’s city movements are short and fixed Immobilities in the city were due to clock time, fixed schedules, and limited transport (with long drives requiring sitting in cars—-because most of the population live outside of the city in ger districts, standing at bus stops and being passengers on buses to navigate the traffic congestion). More sedentary lives were common in Ulaanbaatar but due to women’s work, they did move around extensively in the city. In this study mobilities were associated with freedom to earn a living and thrive in whatever conditions they could.

- Climate Change in conjunction with family economic collapse imposed a background effect on women’s movements and migrations. Arrival times correlated with internal migratory routes for education but also especially around dzuds (severe drought in summer and extreme freezing winters killing herds) especially after 2010. Several women attested to their families losing everything during these times and having few options other than to migrate to the city.

[1] Mongolia has 21 provinces and all except the following four were represented in the study: Bayan-Ulgi, Sukhbaatar, Dundgovi, and Dornogovi. Most participants were born and raised and went to school in in Tuv or surrounding Tuv, especially Arkhangai and Uvurhangai provinces

[2] All 30 women participants were asked how they felt about the interview afterwards, and everyone felt that it was beneficial in some way or form, including being a cathartic experience and/or a means for cultural transmission

[3] For the related study of herder families, ACMS consent forms were signed and recordings were made of most of the herding interviews

A special thank you to the Jack Street Fund for Mongolia which funded both the internal study on Mongolian women migrants and the intraregional study in Korea. I also appreciate all of the continuing support from my research sponsor, Dr. Narantulga (Nara) Bataarjav of the National Academy of Governance who connected to me to IOM contacts: Ms. Myagmar Tsagaan and Ms. Oyunkhishig Yura. I also give a big thanks to Ms. Javzandulam Sodnom (Oko), Mr. Mark Koenig and especially, Ms. Tsolmontuya Altankhundaga (Tsoom), as well as the ACMS leadership, Dr. Charles Krusekopf and Dr. Bolortsetseg Minjin (Bolor) and staff: Ms. Tuvshinzaya Tumenbayar and Dr. Annika Eriksen, and of course, my wonderful ACMS field school fellows and colleagues.

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.